How I would have built Malaysia’s AstraZeneca Vaccine website

This article is inspired by Jonathan Lin’s post on the same topic and how Nike handles their Sneaker Drop sale.

Background#

On 26th May 2021, the Malaysian government opens up vaccination slots to everyone in Kuala Lumpur and major cities in Malaysia. The registration form opens at 12 pm local time. Due to that, thousands (or perhaps millions) of Malaysians are getting ready in front of their computer to fight for the vaccination slot. Only ~1M slots are available to grab among 30M unvaccinated Malaysians.

At the end of the session, everyone was frustrated with the experience. There were a lot of issues but the most notable one was: unable to select a registration state.

Briefly how the website works#

When a user opens the registration website, the user will fill in personal details. Then the user must select the state, location & time for their vaccination slot. Finally, the user will submit their form.

The main issue happens at step #2. In order for the user to select the state, the browser will request the latest list of available slots at http://api.vaksincovid.gov.my/az/?action=listppv. This API endpoint was choking at 12 pm and only works intermittently.

I have written in length about that issue in my Twitter thread

Assumptions & Scoping#

- There were 1M vaccination slot available across the country

- Malaysia has ~30M population

- Assuming 10% of the population are living in urban areas and fighting for the slot, we now have 3M users waiting to register themselves at 12 pm

Given that there’s a 1M vaccination slot, so there’ll be around 1M database writes that will happen in the span of 1 and half hours (they close the registration after 90 minutes). That would be roughly 185 requests per second on average. However, it’s impossible to assume that the traffic is even in that period. We’ll assume the peak traffic 5X of that number, which comes to 925 requests per second.

Assuming 3M users are waiting to use the system, let’s assume that there’ll be 10% of the users are hitting the refresh page at the same time every second for the first few seconds of the launching. There’ll be probably 300,000 requests per second on that listppv endpoint. That’s a lot of RPS. For reference, AWS Cloudfront CDN handled 200M requests per second at peak during Black Friday 2020.

Tolerance#

Let’s assume that we can tolerate stale data for a little duration for served for listppv endpoint. This eventual consistency pattern is pretty common in a distributed system. However, we couldn’t tolerate overbooking as there is a limited number of vaccines at the moment.

Architecture#

Overview#

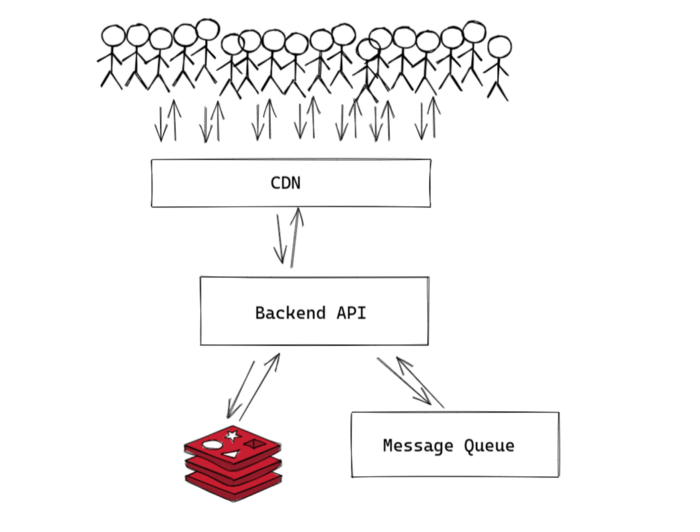

These are the components of this system. Whenever designing a system, always design for scalability, security, and cost-effectiveness. This architecture aims for that.

CDN#

By utilizing CDN correctly, we will be able to:

- Significantly reduce the loads on the origin servers

- Coalesce the requests from users

Cache the API result for a short duration of time like 1 second. Bear in mind that CDN will only cache GET requests but never cache POST requests. In this case, CDN should be absorbing 99% of the GET listppv traffic, leaving the origin server peace of mind.

I have experience helping an e-commerce customer optimizing their API to cache. I can’t remember the what’s figure but it significantly reduces their origin’s workload.

I personally have no better idea than using CDN to serve listppv endpoint. It’s cheap (the transfer rate for CDN is significantly cheaper than VM transfer pricing), scalable, and serverless (no server to manage).

Backend API#

Backend API should be written in Go for its speed. Check out how Randall Degges serve 10,000 requests per second with only several dynos on Heroku.

As the GET listppv requests are mainly handled by CDN, our Backend API will only be busy handling writes. As written in the ‘Assumption & Scoping’ section above, we expect to handle 925 requests per second, which is peanuts for a Go server. For the deployment, I prefer to use Platform as a Service or Container as a Service for simplicity and developer productivity. Any options will do eg. Google Cloud Run, AWS AppRunner, Heroku, etc.

However, it’s important to do capacity planning. It’s important to stress test the computing capacity and always plan for extra buffer. As Backend API is a stateless component, you can easily scale it up and down, but you’ll need to get the number right.

Database#

To handle 925 transactions per second at peak, I personally think that a regular relational database is able to handle this traffic provided that the server is tuned correctly. However, I’m going to use only the Redis in-memory database as the datastore as it’s built for speed. This is heavily inspired by this article.

Assuming that there are 1M user records and each record is 4KB on average, the total storage required for storing all the records is about 4GB which fits in RAM in most Redis servers. Redis servers should be set up with replication and/or AOF data persistence to avoid data loss.

The data has to be denormalized and materialized as we want it to be optimized for reads & writes. User data has to be denormalized where everything should fit in 1 row of a single table and NOT multiple tables. Availability data has to be materialized and no data aggregations are required when retrieving any location’s availability. This gives sweet O(1) speed when retrieving the data. Example how the data looks like:

# Availability

availability:<location>:<date> <availability counter>

availability:pwtc:20210528 1000

availability:pwtc:20210527 1000

# User

user:<mysejahtera id> <hash data>

user:850113021151 firstname fadhil lastname yaacob location pwtc date 20210528

As most of the read operations are absorbed by CDN, our Redis servers are also now only busy processing forms, which is the ideal case. At the end of the day, the data probably is exported to a different database using the ETL process.

Message Queue#

There are many operations that happens right after you finish submitting the form for example sending a notification to your MySejahtera app and I believe many more background tasks. These jobs should be handled asynchronously outside the request cycle.

Implementations#

GET listppv#

When the first user request for listppv endpoint:

- The request will first go to the CDN server

- The CDN server will then forward the request to our origin Backend API

- Our Backend API will query for Redis server for availability for related locations

- Then the backend API will return the result to the CDN server

- CDN server will cache the result in the CDN server with TTL 1 second, then only return to the user

To serve the cached API result, only CDN servers are responsible for it and it doesn’t even hit our Backend API.

For the next 3M users that requests for listppv endpoint in the same second:

- The request will go to the CDN server

- The CDN server will look for the result in the cache storage

- The CDN server will return the result immediately

You can see can the second and consequent requests to listppv endpoint, the requests don’t even hit our origin server! Instead of processing 3M requests per second at peak reading the database repeatedly, the server only processes several times per second for the CDN server to cache the result. This is a big win! I can’t think of any better way to do this other than caching the API result here.

Submitting form#

When a user submits a form, the backend will: Validate the data payload

- Mark the location available slot key with WATCH command

- Get the latest number of the available slot in the location to ensure that we’re not overbooking

- Begin a Redis transaction

- Decrement the availability counter of that location

- Insert new user data as a row

- Commit the transaction

- Publish a message to the message queue

- Return the result

Wrapping the Redis operations into a transaction will ensure that we are able to insert the data atomically.

Updated: Implementation#

I’ve implemented this project and published the Proof of Concept (PoC) in my Github.

Conclusion#

The CDN will absorb most of the GET listppv requests. The drawback is that the data is not real-time and lag 1 second. However, that is good enough provided that we want to serve a very big crowd. For inserting data, we’re using a super-fast in-memory database. The operations are wrapped in a transaction for atomicity and the operations are fast (no table JOINs, aggregation, etc.). I’m happy to hear comments and critics of this architecture.